To walk the talk

As the Public Debate and Participation working group considered how we would ‘walk the talk’ in our ambition to engage better with broader reach, we looked at the methods for our activities. Keen to host an activity that would allow discussion to move beyond the diagnosis of the challenges, towards the generation or ideas and solutions, a ‘hack’ was proposed by members of the group who had experience in this approach.

Originally, ‘hackathons’ were the domain of technology and software companies, crowd-sourcing innovations in programming, but the central method has been adapted to consider a wider range of challenges, including for social policy. Throughout the pandemic, hacks (a shorter version of the classic hackathon) have moved online and used virtual rooms, presentations, pitches and polls to gather together new collaborators to consider challenges… collectively.

Why a Hack?

For the working group, this method allowed us to move into the creative space of knowledge generation, where all participants have equal voice and where the shared ambition is to co-create solutions. Traditionally, the Royal Society of Edinburgh realises its mission of ‘the advancement of learning and useful knowledge’ through the exchange of expertise and knowledge in discussions and with audiences. The experience of the pandemic, and the reflections of the working group have highlighted that the most successful solutions to shared public challenges need to bring technical expertise and public experience together, in a different kind of discussion.

Hosting the RSE’s first Hack, to examine one of the critical themes that has emerged across all of the Post Covid-19 Futures Commission’s work – fake news – and building on members’ experience of running hacks, seemed an excellent opportunity for us to ‘walk the talk’. Several strands of designing the Hack emerged as critical – the theme for the challenge question, the recruitment of participants, support provided to those engaging to ensure an inclusive experience, and the design of the event itself. From the start these considerations interlocked and informed each other, and were thus being adjusted and tweaked until the day of the event.

Testing ideas and being open to the unexpected

We wanted to ensure that the question we were asking was relevant and that it had been tested with the public. For this reason we generated three questions, and then put them to an online public vote.

-

The year is 2040, technology has advanced and everyone has access to the internet. What types of digital tools and technology will allow people to debate important issues respectfully?

-

What kinds of systems can we design to help people know about what’s going on within local and national Government and in media, and how to take part in the debates and decisions that affect their daily life?

-

How can we tackle the spread of “fake news”, and build public knowledge and trust in sound science?

The question which received the most votes in a series of online polls was question three: How can we tackle the spread of “fake news”, and build public knowledge and trust in sound science? Fake news was particularly significant at the time, coming close to the ‘fake news’ inspired storming of the US Capitol. Now we had our focus, we sought to identify routes through which the problem of fake news could be overcome.

Going backwards: from answer to question

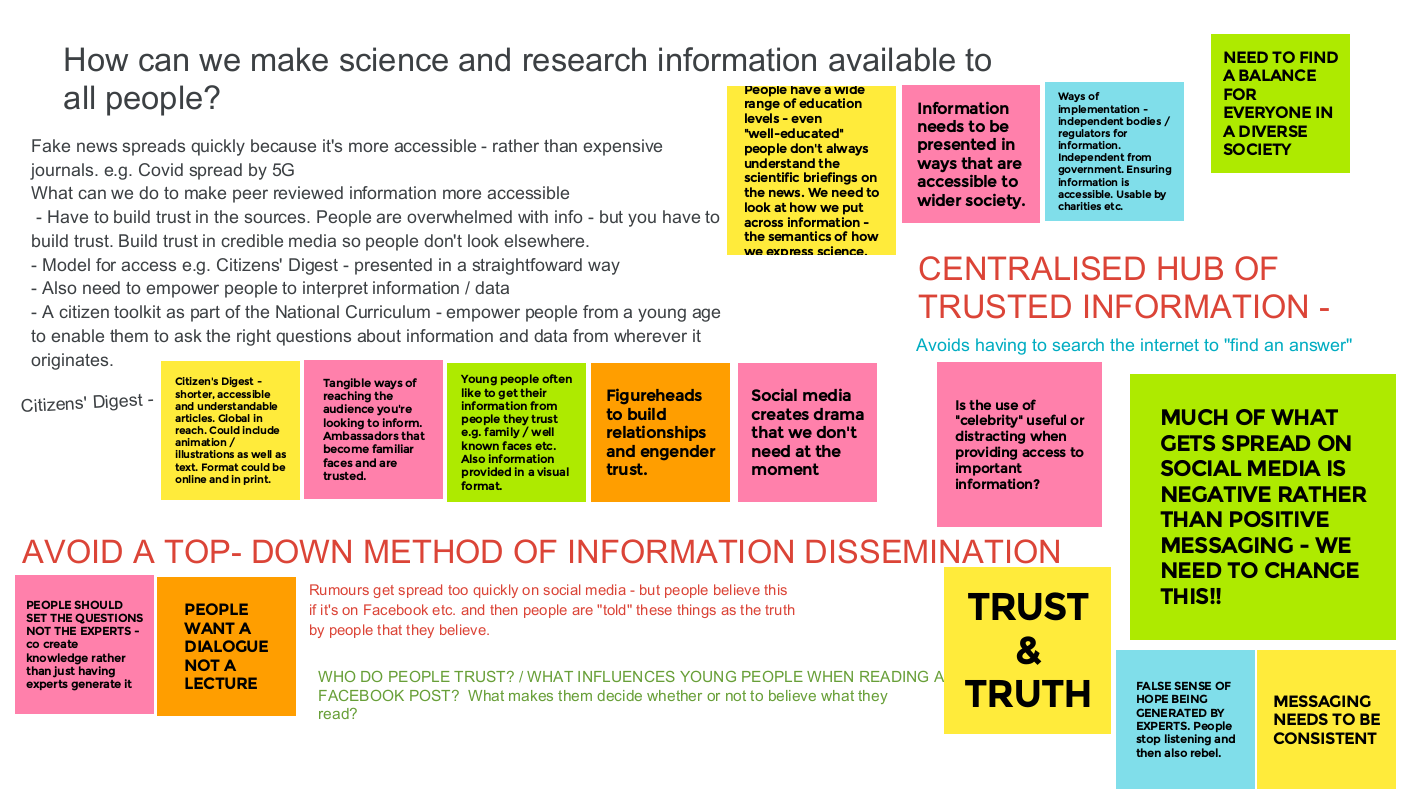

Normally at a Hack identifying the core issues would happen on the day, but we were mindful of screen fatigue and the impact this would have on available time with participants. With only a couple of hours, we needed to predigest some of the key strands of thought. To do this we identified four ‘answers’ which had emerged as interesting ideas on this theme during working group activities, and worked back from those answers to the broader questions they responded to.

This reverse process may seem odd, but it allows much more creative testing of ideas. To illustrate this, one of the problems we identified was that high-quality research is published in academic journals, where that research is reviewed by other academics in a process called peer review. These journals are published behind paywalls, and so are not accessible to citizens unless they have a link to a University. The answer we initially identified was a tech billionaire buying out academic journal publishers and making the research available to everyone. Working back from this, we landed on the question ‘How can we make rigorous, peer-reviewed and scientific data more available?’ which was our second prompt in the Hack. The result was that our starting ‘answer’ didn’t emerge, but lots of other creatively constructed ideas did.

The final four questions which we posed to Hack participants on the day were as follows:

- How can we make rigorous, peer-reviewed and scientific data more available?

- What should Scotland have that could help more people take part in how decisions are made by the Government?

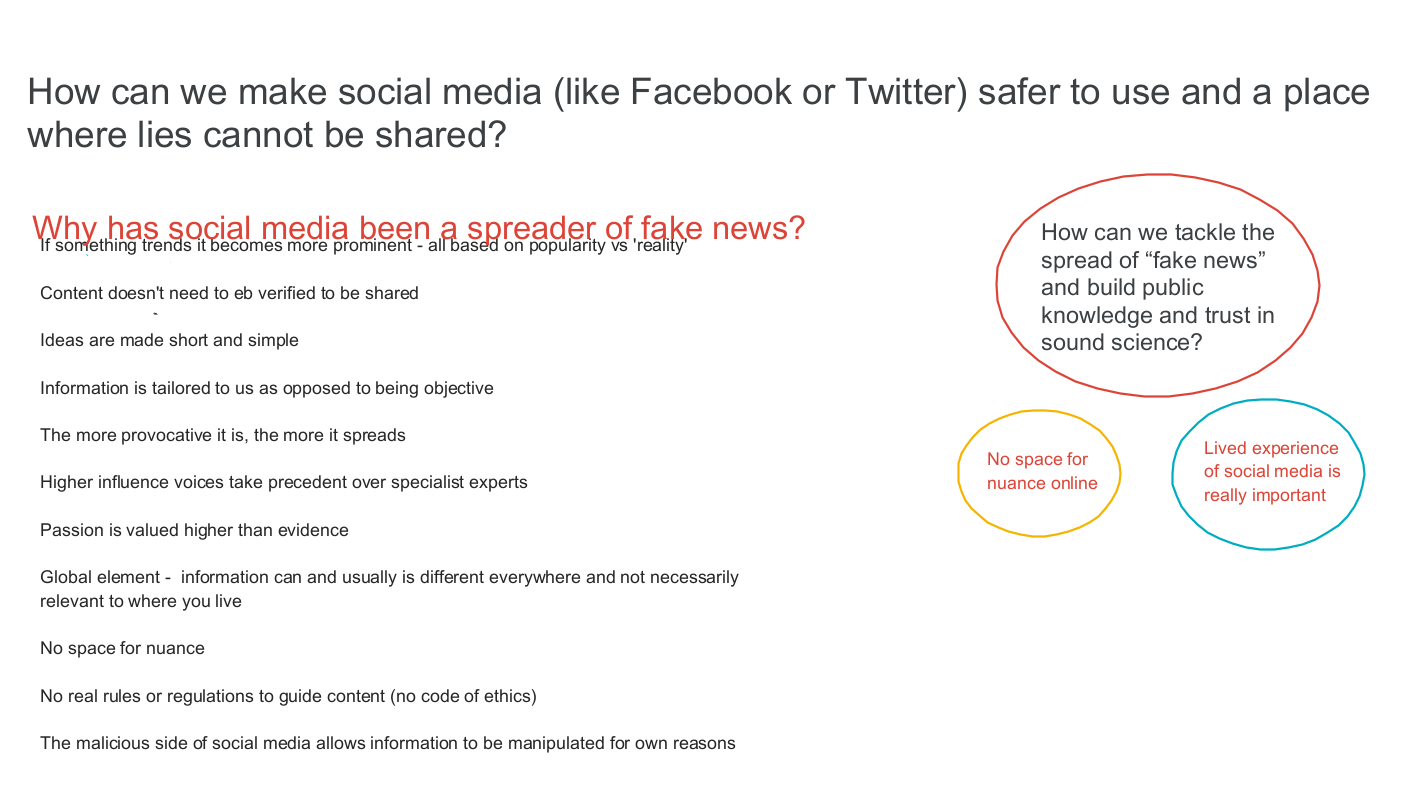

- How can we make social media (like Facebook or Twitter) safer to use and a place where lies cannot be shared?

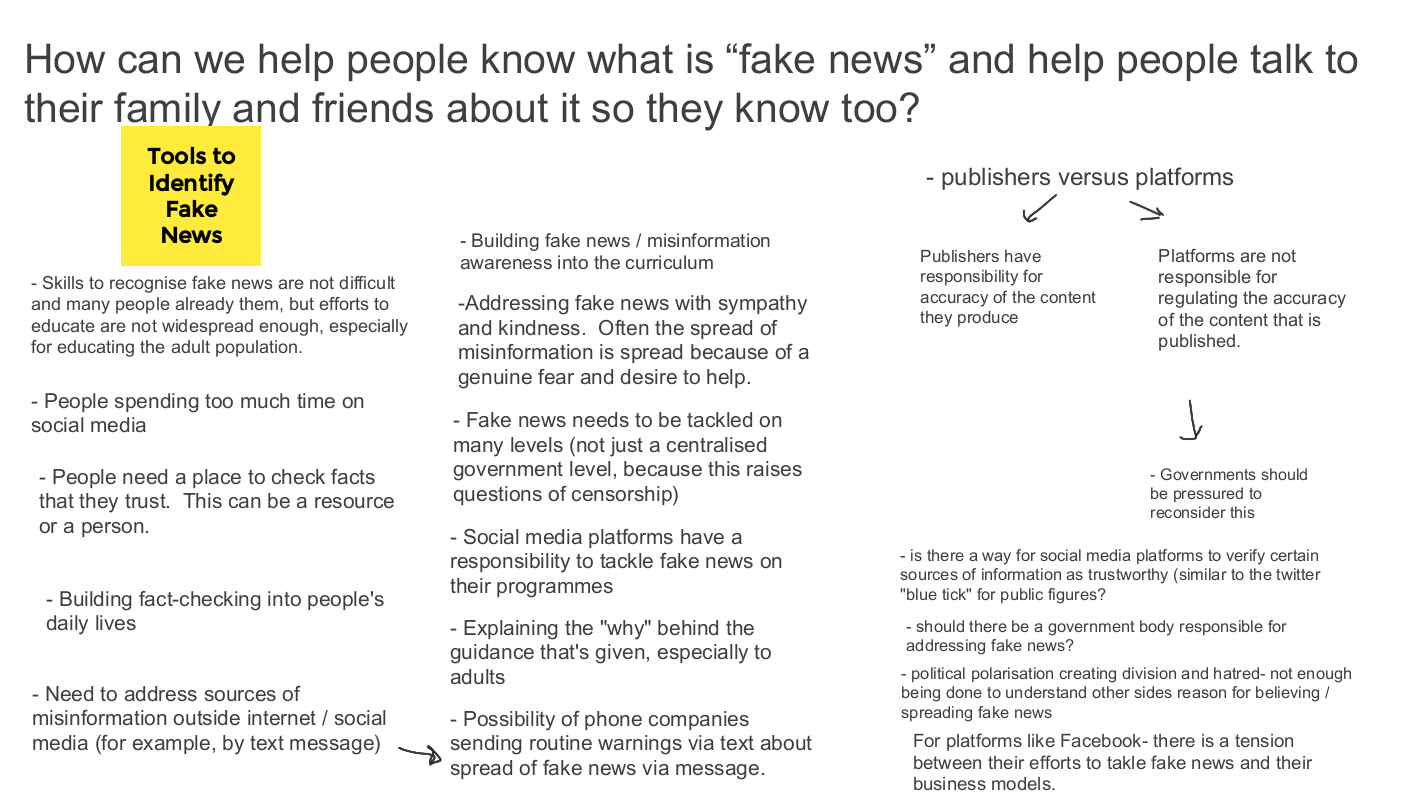

- How can we help people know what is “fake news” and help people talk to their family and friends about it so they know too?

Making the Hack accessible

One of our aims for this hack was to ensure that we brought different kinds of expertise into the collaborative challenge, from both the ‘producer’ and the ‘consumer’ perspectives of science-based news. We used our Commission networks to identify potential participants, and initially assembled a group of science, digital and engagement practitioners and academics. This was then complemented by further participants, including community volunteers and members of third sector organisations, bringing a diversity of backgrounds.

We offered support for any specific needs identified, and were delighted that our assembled group included young people, people with learning disabilities and their support workers. Acknowledging that many of the participants were not attending as part of their ‘day job’ we offered a participation fee to eligible participants. As our participant group took shape, we were able to adjust and refine the materials for the running of the Hack in order to ensure it was accessible for audiences.

In particular, alongside the full Hack Guide which was prepared for participants, we produced an ‘easy read’ version, with the essential information, images and clear succinct advice on what to expect. Thinking that pre-emptively providing screen captioning for the live session would aid our hearing-impaired participants, we discovered that it was visually distracting for other participants. Instead, we learned that our hearing-impaired participants really just needed speakers to slow down a bit. The flexibility to listen to participants as the event is ongoing and adapt these services is key.

The structure of the session

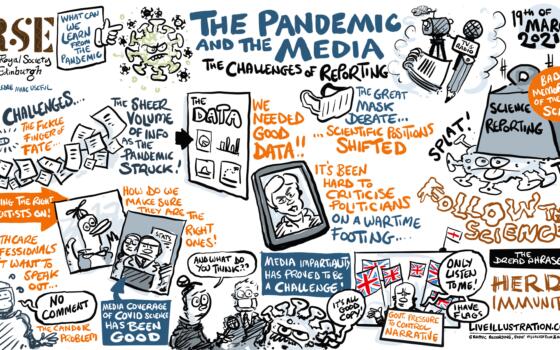

The design of the day was ‘hybrid’ in nature, a compressed version of the fuller Hack structure which would offer more time to more fully explore the theme as well as the possible solutions. Given that participants did not know each other, we opted that the morning online discussion session would be private and for participants only. Working with facilitators and notetakers, we used breakout rooms to have pre-selected groups discuss the four themes and note-take via interactive Jam Boards (which you can see ‘in action’ above).

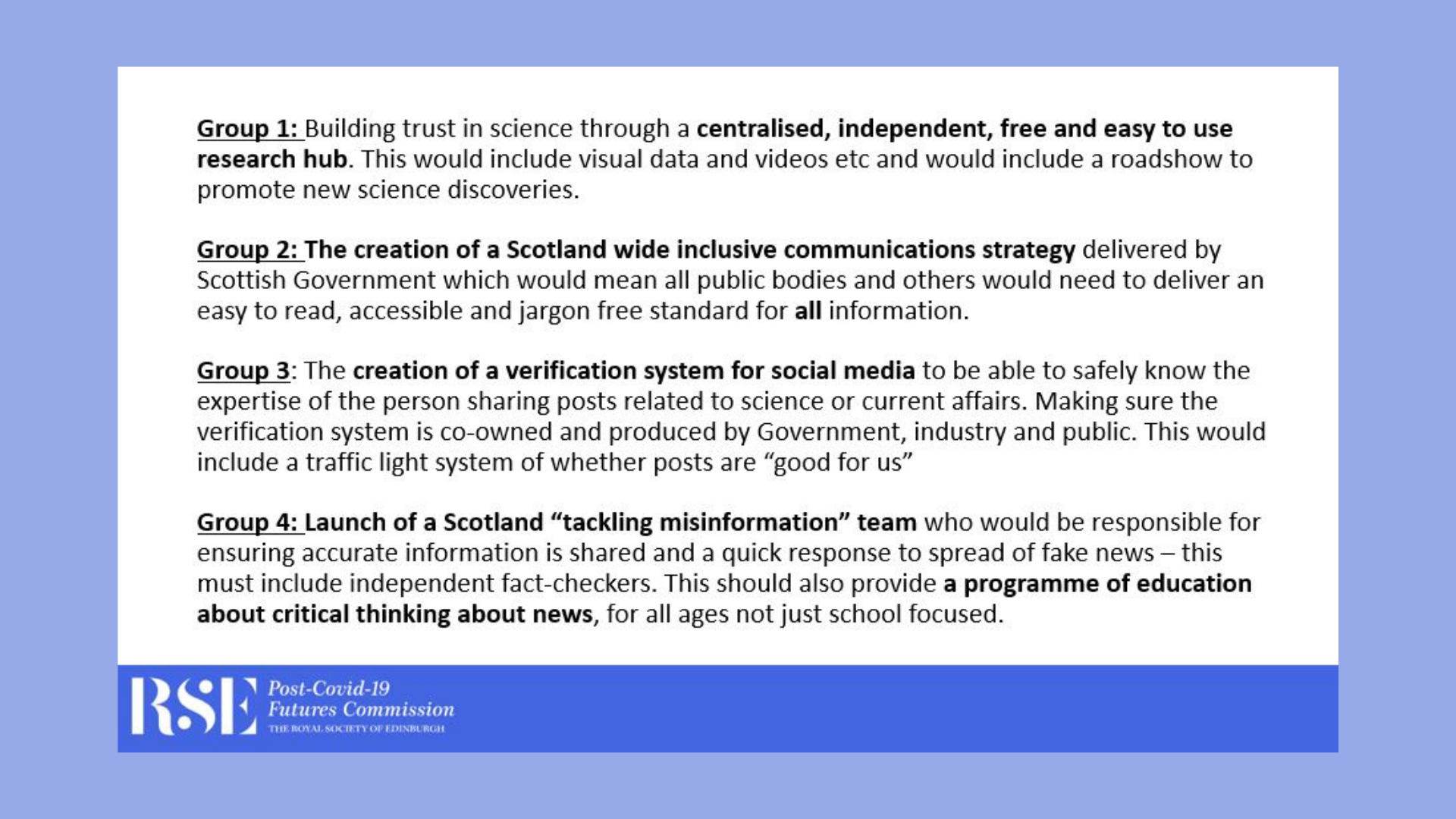

The facilitators then fed back to the Hackers in a short plenary session, and each group identified a presenter to ‘pitch’ their solution to the public polling event in the afternoon. The public poll was an opportunity to air the ideas to a new audience and gauge their popularity. Whilst this was interactive via vote, this was not an engaged discursive session, and so was able to accommodate a much larger audience via Zoom Webinar. After introductions, each solution was presented by a group representative, and the wider audience polled on the solution they preferred. See a summary of each proposed solution presented on the day below – when it came to the vote we had a clear ‘winner’.

The winner of the public vote

The winning proposal was Group 4, responding to the target question: How can we help people know what is “fake news” and help people talk to their family and friends about it so they know too? Here is a summary of their proposal, which was excellently presented during the final public-facing event:

Launch of a Scotland “tackling misinformation” team who would be responsible for ensuring accurate information is shared and a quick response to spread of fake news – this must include independent fact-checkers. This should also provide a programme of education about critical thinking about news, for all ages not just school focused.

Final reflections

As we reflected on the event, we realised that this is a topic that matters across sectors, and groups, but that there aren’t many opportunities for different groups to discuss solutions together. There was a real appetite to have this dialogue and draw from a variety of lived experience and expertise. It is testament to the need for more of these discursive spaces, that it did not feel like any of the groups quite had enough time.

We learned that planning for a Hack requires participant-specific adjustments ‘up to the wire’, so that the challenge theme and the hack design are fine-tuned to the needs of the particular group attending, in order to generate the conditions for everyone involved to fully engage. This style of tailored event design is important always be especially in a Hack – to provide the right environment for fruitful discussion and exchange of ideas. We also learned that there is enthusiasm to discuss the societal challenge of fake news further, and that bringing together both ‘producers’ and ‘consumers’ of science information creates a diverse and productive environment to identify solutions.