Mind your language!

It is 25 years since the Disability Discrimination Act (DDA) received Royal Assent, following hard fought protests and campaigns. The Act placed a positive duty on public bodies to promote equality of opportunity for all disabled people. Ten years ago, the Equality Act identified disability as one of nine protected characteristics that were afforded protection from direct and indirect discrimination, harassment and victimisation. Language, more accurately the use of appropriate language, was a key aspect of these legislative milestones.

And yet, within the first 50 days of the pandemic, we witnessed both casual and deliberate use of language that shook the very foundations of these two pillars of equality and social justice. And now, as we valiantly try to respond and cope with this villainous virus in its third wave, so evidently worse than the initial wave in March last year, we are witness once again to a use of language that, at best, erodes the dignity and human rights of disabled people and, at its worst, completely discriminates against them due to their ‘protected characteristic’.

The earliest example of this normalised discrimination was evident in the very first news reports when the pandemic bore down on us and the first deaths (low in number) were announced. It was commonplace for news reporters to reveal that ‘a further four people had died overnight but it has been confirmed that they all had underlying health conditions.’

It was as if these human tragedies were less concerning as they had ‘underlying health conditions.’ The inference was they don’t really count.

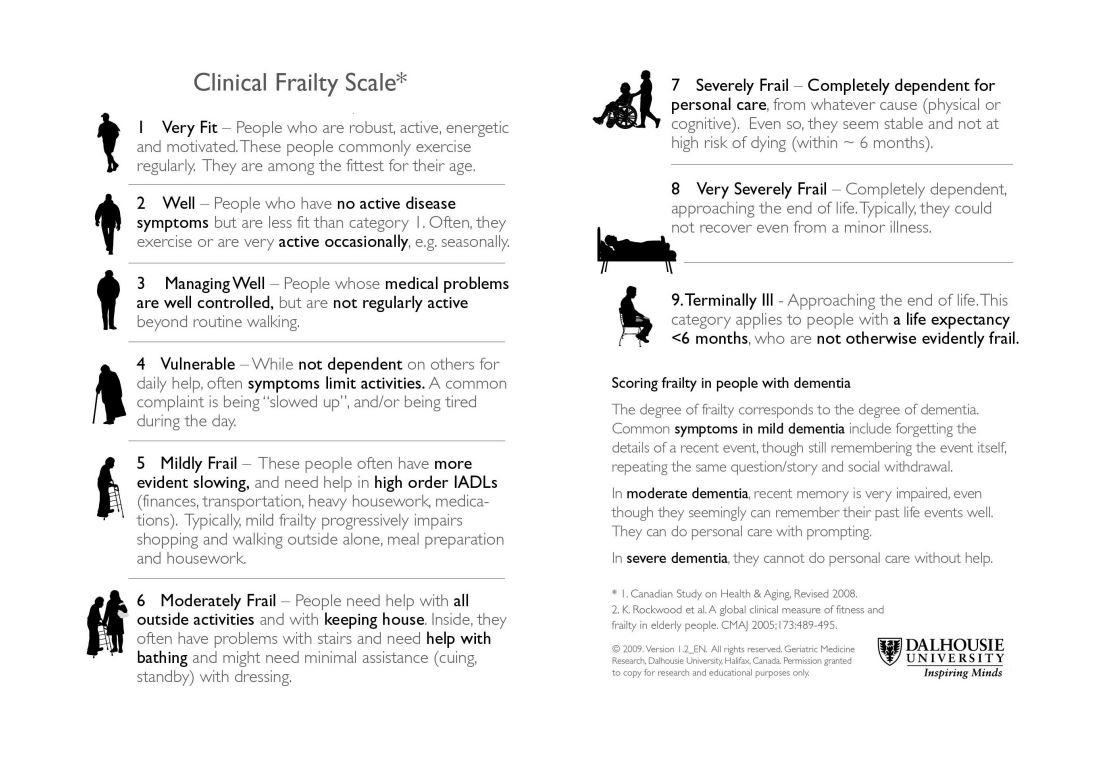

Our worst fears that the term ‘underlying heath conditions’ might include people with learning disabilities were confirmed when reports started reaching us from families that their loved ones appeared not to be getting prioritised for treatment. It appeared that there was inappropriate use of a clinical decision-making tool called the CFS (clinical frailty scale) in acute hospital settings.

The use of acronyms is, in the view of many disabled people, a deliberate mechanism to disguise and normalise the language of exclusion and discrimination. Thankfully, the Scottish Government and NHS leaders heard our voice and our concerns, and new guidance was issued to clinicians that they should not use the ‘clinical frailty scale’ on people with a learning disability who might present for treatment in the pandemic. But worse was to come.

As the first wave began to build, we received a call from a distraught mum of a 41 year old man with Down’s syndrome. This mum was about to celebrate her 80th birthday when she took a call from her GP advising that he was speaking with a number of his ‘vulnerable’ patients suggesting that in anticipation of a Covid hospital admission ‘it might be wise to consider putting a DNR (do not resuscitate) order in place’ for her son. As well as being distraught the mum was confused. ‘Surely there has been a mistake, my son is fit and healthy and has no medical conditions’ – she wondered why the GP was not speaking about her heart condition.

This was not an isolated incident and, once again, we see the use of an acronym to mask a very serious intent. The wholly inappropriate use of the word ‘vulnerable’, which today is in widespread use, frames the perception of disabled people as ‘being less’.

This deficit-based language approach has significantly eroded the progress made over the last 40 years and cannot be allowed to shape discussions around recovery and renewal.

We now know that people with learning disabilities are six times more likely to die if they catch this deadly virus and this figure rises dramatically to ten times more likely if you are an adult with Down’s syndrome. This latter statistic from the study of deaths over the first six months of the pandemic conducted by Oxford University, led the four Chief Medical Officers across the UK to take an immediate decision, in November last year, to place all adults with Down’s syndrome on the shielding list (as they say in Scotland) or on the list of the Clinically Extremely Vulnerable (as they more commonly say in England).

Nothing in this article is intended to be a criticism of those who on a daily, weekly and now monthly basis have worked tirelessly and selflessly in the most stressful and traumatic of settings within the growing number of Covid wards in our hospitals. I simply can’t imagine the pressure they are under and the decisions they are having to make. We owe it to them to ensure that, as they attempt to recover from the trauma that has visited them these past ten months, they know, with confidence, that their care and their decisions were influenced solely by the medical issues presenting and not by some unconscious negative bias about disability.

And that is why we will continue to speak out.

In medical communities they call this ‘diagnostic overshadowing’ and there are endless scholarly articles written about the phenomena – the circumstance when a clinician might ascribe the presenting issues as being related to the disability as opposed to a medical need. It is perhaps the ‘finest’ example of normalising discrimination, born of ignorance.

As we move ahead to build forward differently (we have no desire to build back better; whatever that means), an inclusive approach must prevail. While our actions in this regard will be critical, it is our words, arguably, that will define the success of our early recovery and renewal.

In that regard, we would all do well to mind our language.

Eddie McConnell is Chief Executive of Down’s Syndrome Scotland and Chair of the Scottish Commission for People with a Learning Disability. Two members of his immediate family work in the NHS and two members of his household have been shielding throughout the pandemic, including his 17-year-old son who has Down’s syndrome.

THIS BLOG WAS COMMISSIONED AS PART OF THE PUBLIC DEBATE & PARTICIPATION WORK STRAND.